What we are left with is “the ‘good parts’ version”-a rare understatement in a novel filled with dastardly deeds and thrilling feats of derring-do. Goldman’s Princess Bride is therefore an abridgement, with all of the “other such stuff” having been removed (but summarized in playful asides). “For Morgenstern,” writes Goldman, “the real narrative was not Buttercup and the remarkable things she endures, but, rather, the history of the monarchy and other such stuff.”

When Goldman revisits the novel as an adult, he realizes that his father skipped many hundreds of pages in his reading, much of it historical detail, backstory, and long, tediously satirical passages about Florinese customs: fifty-six pages on a queen’s wardrobe, for instance, or seventy-two pages about the royal training of a princess. Morgenstern, the legendary Florinese writer (Florin being a country “set between where Sweden and Germany would eventually settle”), and read to Goldman as a child by his father, a Florinese immigrant.

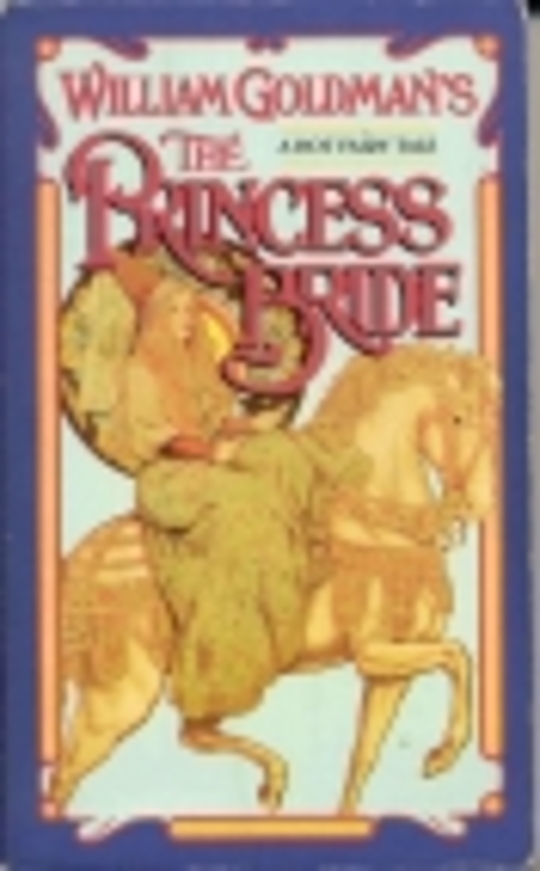

In a thirty-page, first-person introduction, Goldman explains that it was written by S. There is plenty of room for observations of this kind, for “The Princess Bride” is a novel within a novel. But Goldman isn’t interested in satire in fact it is one of the novel’s central motifs that satire is a bloodless, empty exercise, lost on all but the most pretentious, scholarly readers. It’s possible that a suspicious reader might discern certain Nixonian qualities in Humperdinck, Goldman’s vain, conspiratorial, power-hungry prince, or see in Count Rugen, the prince’s diabolical, merciless, hypocritical hatchet man, a medieval Robert Haldeman.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)